Coming Home

Coming Home- The Sydney Swans It went down like a drug deal. As mum and I sat dejected on a bench outside the Melbourne Cricket Ground — our prospects of scoring all but gone — a man in a cap and sunglasses sat down alongside me and took a huge bite out of his burger. […]

Beyond Equal Pay, How Do You Define Equality in The Lineup?

In 2018 there was plenty of righteous celebration — and sadly plenty of comment board grumblings — when the WSL announced pay parity for men and women. Finally. Having never surfed competitively let alone professionally, I often wonder what equality looks like for the everywoman surfer when you step outside the realm of pro surfing. […]

The Legitimacy of Sugar Addiction: My White Powdery Blow

I wrote this a while ago, but I’ve been too shit scared to share it with people I know. I guess I’ve been scared that people might think my story is lame and the idea of being addicted to sugar and needing to let it go entirely is a hoax. But those are the thoughts that […]

Nick Carroll on Surfing and Women Surfers of the 70’s and 80’s

With a shoulder span that rivals his height, it’s clear Nick Carroll has spent a fair whack of time paddling around the world’s lineups over the last half century. He’s lived a rich surfing life and has witnessed decades of iconic surfing moments and cultural shifts. I couldn’t think of a keener mind to pick and […]

What Are Lawnmower Parents Mowing Down?

We’re all familiar with the overhead drone of the helicopter parent, poised to swoop when their offspring are in a spot of bother, but have you come across the agitating whir of the lawnmower parent?

What’s In A Name?

What’s in a name? Not much according to some and a whole lot according to others, I learned as I was handed the whole gamut of opinions when I changed my name last year. I ditched my married name to reclaim my maiden name in the absence of getting a divorce— my marriage still intact.

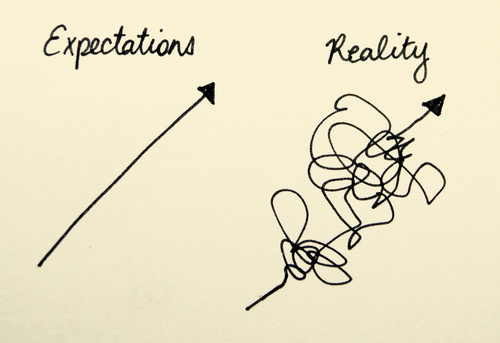

Not Such Great Expectations

It might be sacrilege to suggest to some— particularly those perpetually stoked and sunny types— but I don’t always come in from a surf feeling better than when I paddled out. I’m reticent to admit it— nobody likes a Debbie Downer— but occasionally I come in feeling downright pissed.

Me too? Was It Really Something?

As the protective veil that shrouded Harvey Weinstein’s misdeeds fell before his and the world’s eyes, and women from pole to pole began to post their #metoo experiences I was roused to post #metoo on my Facebook wall. A collective of female voices surged into a crescendo as women put their experiences of sexual harassment […]

Giving Up

I don’t know about you, but I can be quite the slow learner. Continually pushing shit up a hill until I realize what I’m doing isn’t working out very well. Einstein posited that insanity was doing the same thing over and over and expecting a different result. That said, it’d be fair to question my […]

It’s Not Personal

My shins smashed into the deck of my board as I tried to pop up. Again. The sting buzzed through them as I bailed into the whitewater and screamed beneath the surface.