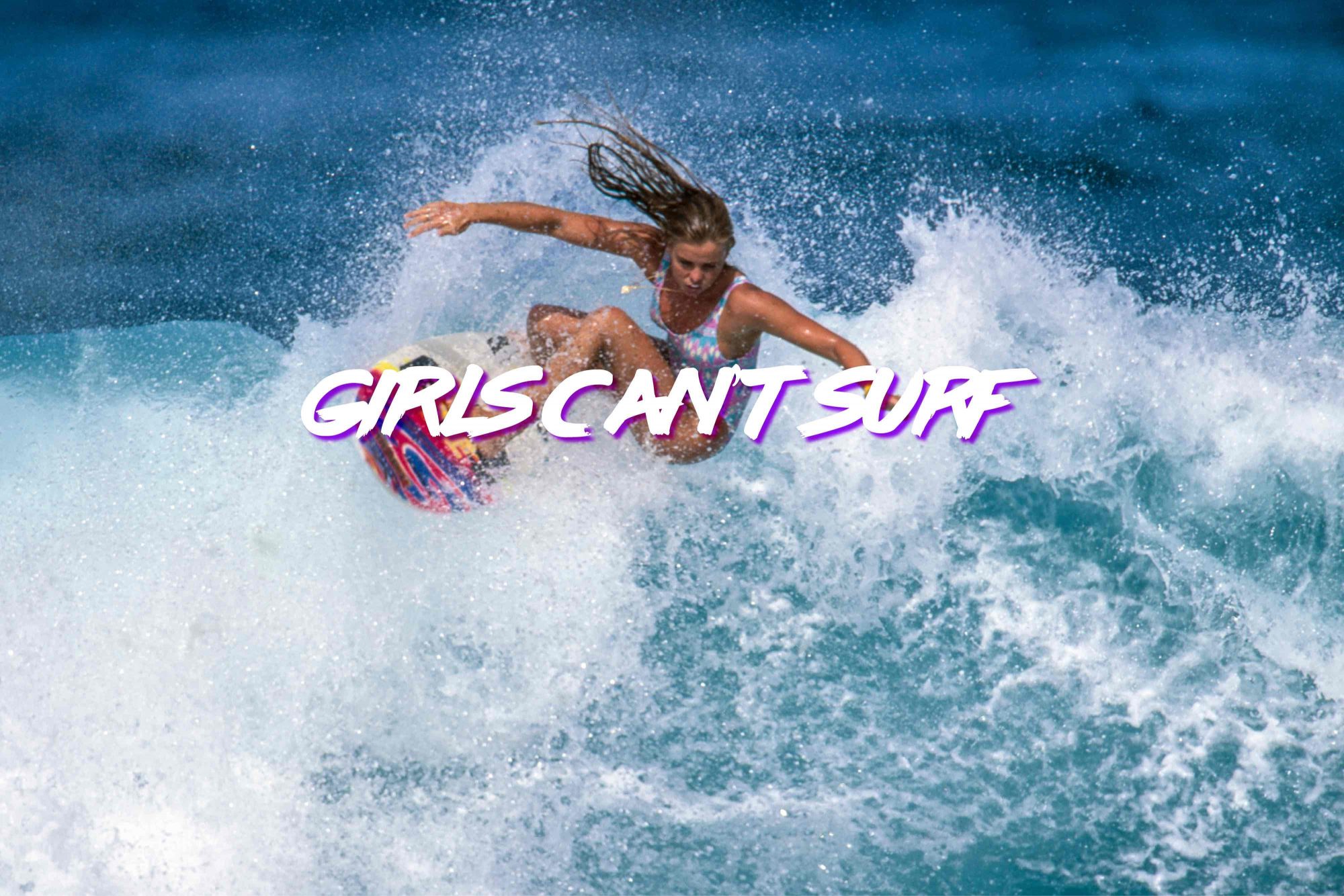

At a time when Salt-N-Pepa were urging mobs to Push it on the dancefloor, an eclectic bunch of hungry surfing women were truly pushin’ it against the status quo of the 1980s surf world. Pushing for a place in the lineup. And pushing for a place — a legitimate place — in pro surfing. Because they were told overtly they didn’t belong. Girls can’t surf after all.

The recently released Girls Can’t Surf tells the story of these women: Pam Burridge, Jodie Cooper, Pauline Menzcer, Layne Beachley, Frieda Zamba and Wendy Botha. And it is a cracker.

The beauty of this film lies in the willingness of the women featured to really go there. A dive into the chauvinistic echo chamber of 80s surf culture is bolstered by intimate personal narratives; a film and book could and should be made and written about each woman alone. Jodie Cooper’s sexuality. Pam Burridge’s alcoholism and anorexia. Pauline Menczer’s rheumatoid arthritis. They get real in a way that’s entirely relatable for viewers of all ages and backgrounds. You don’t have to be a fan of surfing to enjoy this movie. Just a fan of human perseverance.

Their candid remarks about surfing against each other is a highlight. This is hysterical and the still simmering tensions palpable. Here’s voting for a World Master’s Championship heat between Layne and Lisa.

I’ll stop short of re-hashing the movie’s narrative here. The thing is: you should go see it. It is brilliant storytelling and Producers Chris Nelius and Mikaela Perske have made a fundamentally important contribution to surfing culture.

Instead I’m keener to explore questions the movie’s release raises for me. Like, why is there a huge void when it comes to the documentation of women from surfing’s past? How does this relate to who is telling the stories of women’s surf history? And what needs to change in this regard?

In the film, Nick Carroll and Jamie Brisick voice their perceptions as legitimate authorities on surf culture. Both men are acutely intelligent and empathetic, and their observations add tremendous value to the movie. Nick said in a recent episode of The Lineup podcast that when asked he was initially apprehensive to be involved in the movie as it wasn’t his story to tell. But he was a valid and obvious choice having been a veteran surf writer who observed these women up close over many years.

Why not feature a woman surf writer? Because there were none. All of surfing’s experts are men. The editors, writers, historians, movie makers, photographers and storytellers. The loudest voices belong to men. Nick. Jamie. Matt Warshaw. Tim Baker. Sean Doherty. Phil Jarratt. Derek Hynd.

There is nothing inherently wrong with that. Men can and should tell the stories of women and women that of men. But the absence of women contributors over many decades is a big part of why women in surf history are so poorly documented and why there is so little footage of women surfing in the 70s, 80s and even 90s in comparison to men. It’s unlikely a calculated exclusion, it’s just that at the editing table of a surf mag women were — and to some degree still are — mostly an afterthought.

Even today, women have very little presence as storytellers in the mainstream surf media platforms that have broad audiences. A lot of women have taken matters into their own hands with a surge in independent magazines, films and social media accounts that focus on sharing women’s stories. But take a look at the big forecasting sites with lots of traffic and see how many women contributors you can find in regard writers and photographers. Then take a look at the surf magazine websites. You’ll find some. But percentage wise it’s very low. And this does matter.

We need more diversity in the creators of content. Not only is this reflected in a lack of gender diversity in subjects we see, but it can impact the way a story is told. The success of Girls Can’t Surf relies on the featured women having the space to tell their own stories. The spotlight is squarely on them. But what about when the storyteller projects their own gendered biases and ignorance onto their subject? It’s dangerous territory which can misrepresent the truth and legacy of surfing women.

One example of this would be Phil Jarratt’s portrayal of Isma Amor — one of Australia’s first women surfers — in his book Surfing Australia: A Complete History of Surfboard Riding in Australia. Jarratt is a respected surf writer and historian whose work is frequently cited. He describes fifteen year old Isma as a “sultry seductress.” He sexualises an adolescent and defines her in relationship to men. And that’s the extent of his description. No details about Amor surfing, what type of board she rode etc. What was his portrayal based on? Not facts that’s for certain. The baseless narrative he chose to present is a harmful one.

And Jarratt’s blunder is an acute one. But having stories told over and over through the male lens can lead to more subtle biases in depiction. There are certain angles of thought that will not occur to men because it is not within the realm of their lived experience. I’ve read articles by high profile male surf writers in the last year proclaiming that equality is here; women are now being paid equally in the pro ranks and when they look around in the lineup numbers of women match that of men. It’s a rather simplistic view of a complex topic. I, like many women have felt wholly equal in certain lineups and contexts and conversely, I’ve had experiences where I have felt like anything but. The last thing I want to read is a bloke telling me what fantastic egalitarianism I am experiencing in the surf when that is not always the case.

Having more women storytellers will result in a more true and rich image of surfing. It will allow us to see more stories about women. Girls Can’t Surf tells the 80s story of women’s pro surfing. Now let’s hear about the 70s, 60s and 50s rather than using that space for another Michael Peterson feature, or whatever other male icon we’ve heard about ad nauseum.

Let’s hear about the Women’s Surfing Hui based in Hawaii in the 70s: Patti Paniccia, Linda McCrerey, Jeannie Chesser, Rell Sunn, Laola Lake, Claudia Nuuhiwa, Elaine Davis and Linda Divoli. This bunch of women spearheaded the formation of women’s pro surfing. It wouldn’t exist without them.

And what about the classic stylists of the 60s: Phyllis O’Donell, Linda Benson, Joyce Hoffman, Josette Lagardere and Joey Hamasaki to name only a handful.

The skill of the 50s waterwomen was next level. In addition to being adept surfers many of these women were winning swimmers and divers like Marge Calhoun and Mary Ann Hawkins. Anona Napoleon was a mean kayaker who just missed the Olympics and was one of the first women to cross the Molokai to Oahu channel in a women’s canoe team.

Isabel Letham and Isma Amor were in their teens amongst the first girls to surf in Australia.

Hawaiian Princess Victoria Ka‘iulani surfed in late 1800s Honolulu when surfing was discouraged full stop, but even more so for women given the colonial expectations of conforming to a feminine ideal. Surfing was considered a masculine pursuit.

Since day dot women have been surfing. When explorers arrived in Hawaii a recurrent observation in their journal entries was that women surfed in equal numbers in comparison to their male counterparts and their skills also matched that of the men. There was no gender divide in the water.

Gotta keep pushin’ for the stories of these women to be told and for greater diversity in who tells them.